UCI Data Benchmarking

In this notebook, we will show how to apply GPJax on a benchmark UCI regression problem. These kind of tasks are often used in the research community to benchmark and assess new techniques against those already in the literature. Much of the code contained in this notebook can be adapted to applied problems concerning datasets other than the one presented here.

# Enable Float64 for more stable matrix inversions.

from jax import config

import jax.numpy as jnp

import jax.random as jr

from jaxtyping import install_import_hook

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.metrics import (

mean_squared_error,

r2_score,

)

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from examples.utils import use_mpl_style

config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)

with install_import_hook("gpjax", "beartype.beartype"):

import gpjax as gpx

from gpjax.parameters import Parameter

# set the default style for plotting

use_mpl_style()

cols = mpl.rcParams["axes.prop_cycle"].by_key()["color"]

key = jr.key(42)

Data Loading

We'll be using the Yacht dataset from the UCI machine learning data repository. Each observation describes the hydrodynamic performance of a yacht through its resistance. The dataset contains 6 covariates and a single positive, real valued response variable. There are 308 observations in the dataset, so we can comfortably use a conjugate regression Gaussian process here (for more more details, checkout the Regression notebook).

try:

yacht = pd.read_fwf("data/yacht_hydrodynamics.data", header=None).values[:-1, :]

except FileNotFoundError:

yacht = pd.read_fwf(

"docs/_examples/data/yacht_hydrodynamics.data", header=None

).values[:-1, :]

X = yacht[:, :-1]

y = yacht[:, -1].reshape(-1, 1)

Preprocessing

With a dataset loaded, we'll now preprocess it such that it is more amenable to modelling with a Gaussian process.

Data Partitioning

We'll first partition our data into a training and testing split. We'll fit our Gaussian process to the training data and evaluate its performance on the test data. This allows us to investigate how effectively our Gaussian process generalises to out-of-sample datapoints and ensure that we are not overfitting. We'll hold 30% of our data back for testing purposes.

Response Variable

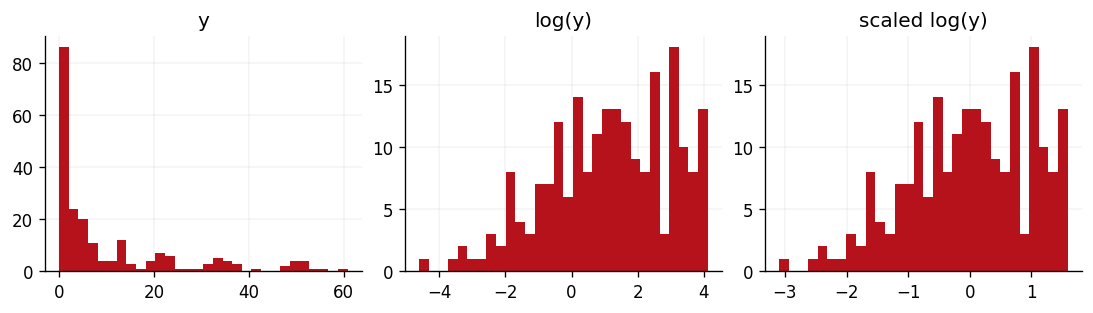

We'll now process our response variable . As the below plots show, the data has a very long tail and is certainly not Gaussian. However, we would like to model a Gaussian response variable so that we can adopt a Gaussian likelihood function and leverage the model's conjugacy. To achieve this, we'll first log-scale the data, to bring the long right tail in closer to the data's mean. We'll then standardise the data such that is distributed according to a unit normal distribution. Both of these transformations are invertible through the log-normal expectation and variance formulae and the the inverse standardisation identity, should we ever need our model's predictions to be back on the scale of the original dataset.

For transforming both the input and response variable, all transformations will be done with respect to the training data where relevant.

log_ytr = np.log(ytr)

log_yte = np.log(yte)

y_scaler = StandardScaler().fit(log_ytr)

scaled_ytr = y_scaler.transform(log_ytr)

scaled_yte = y_scaler.transform(log_yte)

We can see the effect of these transformations in the below three panels.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(9, 2.5))

ax[0].hist(ytr, bins=30, color=cols[1])

ax[0].set_title("y")

ax[1].hist(log_ytr, bins=30, color=cols[1])

ax[1].set_title("log(y)")

ax[2].hist(scaled_ytr, bins=30, color=cols[1])

ax[2].set_title("scaled log(y)")

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'scaled log(y)')

Input Variable

We'll now transform our input variable to be distributed according to a unit Gaussian.

x_scaler = StandardScaler().fit(Xtr)

scaled_Xtr = x_scaler.transform(Xtr)

scaled_Xte = x_scaler.transform(Xte)

Model fitting

With data now loaded and preprocessed, we'll proceed to defining a Gaussian process model and optimising its parameters. This notebook purposefully does not go into great detail on this process, so please see notebooks such as the Regression notebook and Classification notebook for further information.

Model specification

We'll use a radial basis function kernel to parameterise the Gaussian process in this notebook. As we have 5 covariates, we'll assign each covariate its own lengthscale parameter. This form of kernel is commonly known as an automatic relevance determination (ARD) kernel.

In practice, the exact form of kernel used should be selected such that it represents your understanding of the data. For example, if you were to model temperature; a process that we know to be periodic, then you would likely wish to select a periodic kernel. Having Gaussian-ised our data somewhat, we'll also adopt a Gaussian likelihood function.

n_train, n_covariates = scaled_Xtr.shape

kernel = gpx.kernels.RBF(

active_dims=list(range(n_covariates)),

variance=jnp.var(scaled_ytr),

lengthscale=0.1 * jnp.ones((n_covariates,)),

)

meanf = gpx.mean_functions.Zero()

prior = gpx.gps.Prior(mean_function=meanf, kernel=kernel)

likelihood = gpx.likelihoods.Gaussian(num_datapoints=n_train)

posterior = prior * likelihood

Model Optimisation

With a model now defined, we can proceed to optimise the hyperparameters of our model using Scipy.

training_data = gpx.Dataset(X=scaled_Xtr, y=scaled_ytr)

opt_posterior, history = gpx.fit_scipy(

model=posterior,

objective=lambda p, d: -gpx.objectives.conjugate_mll(p, d),

train_data=training_data,

trainable=Parameter,

)

print(-gpx.objectives.conjugate_mll(opt_posterior, training_data))

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: -6.805748

Iterations: 22

Function evaluations: 33

Gradient evaluations: 33

-6.805747503867565

Prediction

With an optimal set of parameters learned, we can make predictions on the set of data that we held back right at the start. We'll do this in the usual way by first computing the latent function's distribution before computing the predictive posterior distribution.

latent_dist = opt_posterior(scaled_Xte, training_data)

predictive_dist = likelihood(latent_dist)

predictive_mean = predictive_dist.mean

predictive_stddev = jnp.sqrt(predictive_dist.variance)

Evaluation

We'll now show how the performance of our Gaussian process can be evaluated by numerically and visually.

Metrics

To numerically assess the performance of our model, two commonly used metrics are root mean squared error (RMSE) and the R2 coefficient. RMSE is simply the square root of the squared difference between predictions and actuals. A value of 0 for this metric implies that our model has 0 generalisation error on the test set. R2 measures the amount of variation within the data that is explained by the model. This can be useful when designing variance reduction methods such as control variates as it allows you to understand what proportion of the data's variance will be soaked up. A perfect model here would score 1 for R2 score, whereas predicting the data's mean would score 0 and models doing worse than simple mean predictions can score less than 0.

rmse = mean_squared_error(y_true=scaled_yte.squeeze(), y_pred=predictive_mean)

r2 = r2_score(y_true=scaled_yte.squeeze(), y_pred=predictive_mean)

print(f"Results:\n\tRMSE: {rmse: .4f}\n\tR2: {r2: .2f}")

Results:

RMSE: 0.0102

R2: 0.99

Both of these metrics seem very promising, so, based off these, we can be quite happy that our first attempt at modelling the Yacht data is promising.

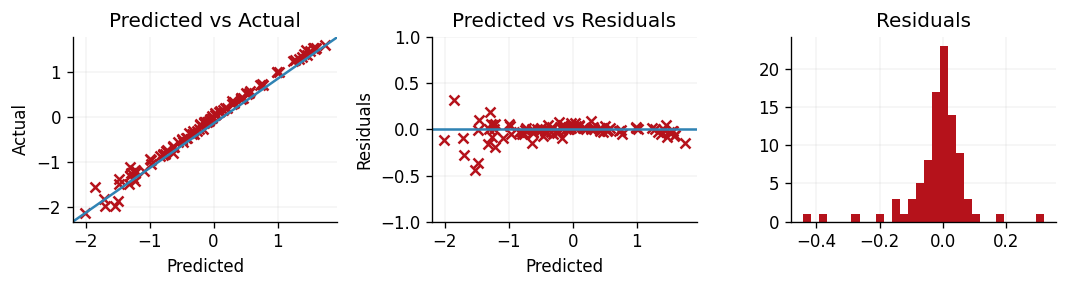

Diagnostic plots

To accompany the above metrics, we can also produce residual plots to explore exactly where our model's shortcomings lie. If we define a residual as the true value minus the prediction, then we can produce three plots:

- Predictions vs. actuals.

- Predictions vs. residuals.

- Residual density.

The first plot allows us to explore if our model struggles to predict well for larger or smaller values by observing where the model deviates more from the line . In the second plot we can inspect whether or not there were outliers or structure within the errors of our model. A well-performing model would have predictions close to and symmetrically distributed either side of . Such a plot can be useful for diagnosing heteroscedasticity. Finally, by plotting a histogram of our residuals we can observe whether or not there is any skew to our residuals.

residuals = scaled_yte.squeeze() - predictive_mean

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3, figsize=(9, 2.5), tight_layout=True)

ax[0].scatter(predictive_mean, scaled_yte.squeeze(), color=cols[1])

ax[0].plot([0, 1], [0, 1], color=cols[0], transform=ax[0].transAxes)

ax[0].set(xlabel="Predicted", ylabel="Actual", title="Predicted vs Actual")

ax[1].scatter(predictive_mean.squeeze(), residuals, color=cols[1])

ax[1].plot([0, 1], [0.5, 0.5], color=cols[0], transform=ax[1].transAxes)

ax[1].set_ylim([-1.0, 1.0])

ax[1].set(xlabel="Predicted", ylabel="Residuals", title="Predicted vs Residuals")

ax[2].hist(np.asarray(residuals), bins=30, color=cols[1])

ax[2].set_title("Residuals")

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Residuals')

From this, we can see that our model is struggling to predict the smallest values of the Yacht's hydrodynamic and performs increasingly well as the Yacht's hydrodynamic performance increases. This is likely due to the original data's heavy right-skew, and successive modelling attempts may wish to introduce a heteroscedastic likelihood function that would enable more flexible modelling of the smaller response values.

System configuration

Author: Thomas Pinder

Last updated: Mon Oct 20 2025

Python implementation: CPython

Python version : 3.11.13

IPython version : 9.5.0

matplotlib: 3.10.6

pandas : 2.3.2

gpjax : 0.13.0

jax : 0.7.1

numpy : 2.3.2

sklearn : 1.7.1

jaxtyping : 0.3.2

Watermark: 2.5.0