Orthogonal Additive Kernels

In this notebook we demonstrate the Orthogonal Additive Kernel (OAK) of Lu, Boukouvalas & Hensman (2022). OAK provides an interpretable additive Gaussian process model that decomposes the target function into main effects and interaction terms, whilst remaining a valid positive-definite kernel. The key ingredients are:

- A per-dimension constrained SE kernel that is orthogonal to the constant function under the input density.

- Newton-Girard recursion to efficiently combine these constrained kernels into elementary symmetric polynomials up to a chosen interaction order.

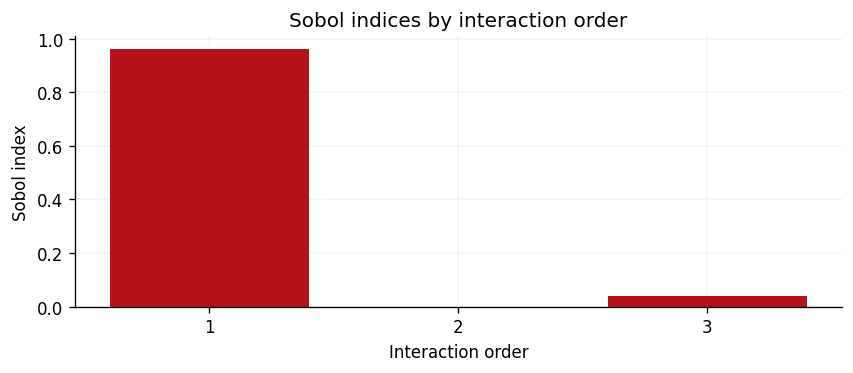

- Analytic Sobol indices that quantify the relative importance of each interaction order, enabling practitioners to understand which features and feature interactions drive the model's predictions.

We illustrate the full workflow on the UCI Auto MPG dataset.

# Enable Float64 for more stable matrix inversions.

from jax import config

config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)

from examples.utils import use_mpl_style

import jax.numpy as jnp

import jax.random as jr

from jaxtyping import install_import_hook

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

with install_import_hook("gpjax", "beartype.beartype"):

import gpjax as gpx

from gpjax.kernels.additive import (

OrthogonalAdditiveKernel,

predict_first_order,

rank_first_order,

sobol_indices,

)

from gpjax.parameters import Parameter

key = jr.key(123)

use_mpl_style()

colours = mpl.rcParams["axes.prop_cycle"].by_key()["color"]

Mathematical background

Additive GP decomposition

A standard GP with a single kernel \(k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x}')\) treats all input dimensions jointly. An additive GP instead decomposes the latent function as

where \(f_0\) is a constant offset, \(f_d\) are first-order (main) effects, \(f_{dd'}\) are second-order interactions, and so on. Truncating at a maximum interaction order \(\tilde{D} \le D\) yields a model that scales gracefully whilst retaining interpretability.

The identifiability problem

A naive additive decomposition is unidentifiable: one can freely shift mass between the constant term and a main effect, or between a main effect and an interaction. Lu et al. resolve this by requiring each component to be orthogonal to all lower-order components under the input density \(p(\mathbf{x})\). In particular, the first-order components satisfy

Constrained SE kernel

Assuming a standard normal input density \(p(x_d) = \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\), the orthogonality constraint can be enforced analytically. The constrained SE kernel is

where \(k(x,y) = \sigma^2 \exp\!\bigl(-\tfrac{(x-y)^2}{2\ell^2}\bigr)\) is the standard SE kernel with lengthscale \(\ell\) and variance \(\sigma^2\). The subtracted projection term removes the component of \(k\) that lies along the constant function under the \(\mathcal{N}(0,1)\) measure.

Newton-Girard recursion

The additive kernel across all interaction orders up to \(\tilde{D}\) is

where \(e_\ell\) denotes the \(\ell\)-th elementary symmetric polynomial and \(\sigma_\ell^2\) are learnable order variances. Computing \(e_\ell\) directly via the combinatorial definition would be prohibitively expensive; instead GPJax uses the Newton-Girard identities which express \(e_\ell\) recursively in terms of power sums \(s_k = \sum_{d=1}^D z_d^k\):

Sobol indices

Once the model is fitted, the relative importance of each interaction order can be quantified via Sobol indices. The Sobol index for order \(d\) is

where \(\boldsymbol{\alpha} = (K + \sigma_n^2 I)^{-1}\mathbf{y}\) and \(E_d\) is the matrix-level elementary symmetric polynomial of the per-dimension integral matrices (see Appendix G.1 of the paper).

Dataset

We use the UCI Auto MPG dataset, which contains fuel consumption data for 392 cars described by 7 continuous features (cylinders, displacement, horsepower, weight, acceleration, model year, and origin).

Because the OAK kernel's constrained form assumes a standard normal input density (\(\mu = 0\), \(\sigma^2 = 1\)), we fit a per-feature normalising flow that maps each marginal to an approximately standard normal distribution. Targets are z-score standardised. This transformation of the inputs data is crucial for the OAK model to work correctly, as the orthogonality constraint is defined with respect to the input density.

from ucimlrepo import fetch_ucirepo

auto_mpg = fetch_ucirepo(id=9)

X_raw = auto_mpg.data.features

y_raw = auto_mpg.data.targets

# Drop rows with missing values

complete_rows = ~(X_raw.isna().any(axis=1) | y_raw.isna().any(axis=1))

X_all = X_raw[complete_rows].values.astype(np.float64)

y_all = y_raw[complete_rows].values.astype(np.float64)

feature_names = list(X_raw.columns)

num_features = X_all.shape[1]

print(f"Dataset: {X_all.shape[0]} observations, {num_features} features")

print(f"Features: {feature_names}")

Dataset: 392 observations, 7 features

Features: ['displacement', 'cylinders', 'horsepower', 'weight', 'acceleration', 'model_year', 'origin']

Normalising flow and train/test split

The constrained SE kernel assumes \(p(x_d) = \mathcal{N}(0,1)\). Simple z-scoring removes the first two moments but cannot correct skewness or heavy tails. We therefore fit a lightweight per-feature normalising flow (Shift → Log → Standardise → SinhArcsinh) that maps each marginal to an approximately standard normal distribution.

y_mean, y_std = y_all.mean(axis=0), y_all.std(axis=0)

y_standardised = (y_all - y_mean) / y_std

num_observations = y_standardised.shape[0]

key, split_key = jr.split(key)

permutation = jr.permutation(split_key, num_observations)

num_train = int(0.8 * num_observations)

train_idx = permutation[:num_train]

test_idx = permutation[num_train:]

y_train = jnp.array(y_standardised[train_idx])

y_test = jnp.array(y_standardised[test_idx])

X_train_original = X_all[train_idx]

X_test_original = X_all[test_idx]

flows = fit_all_normalising_flows(jnp.asarray(X_train_original))

def apply_flows(X_original: np.ndarray) -> jnp.ndarray:

"""Transform each feature column through its fitted normalising flow."""

return jnp.column_stack(

[flows[d](jnp.asarray(X_original[:, d])) for d in range(num_features)]

)

X_train = apply_flows(X_train_original)

X_test = apply_flows(X_test_original)

train_data = gpx.Dataset(X=X_train, y=y_train)

test_data = gpx.Dataset(X=X_test, y=y_test)

Fitting an OAK GP

We create \(D\) independent RBF base kernels, one per input dimension, each

operating on a single dimension via active_dims=[i]. These are wrapped

inside OrthogonalAdditiveKernel with max_order=D (i.e. we allow all

interaction orders). The kernel is then used in a standard conjugate GP

workflow: define a prior and Gaussian likelihood, form the posterior, and

optimise hyperparameters by maximising the marginal log-likelihood.

base_kernels = [gpx.kernels.RBF(active_dims=[i]) for i in range(num_features)]

oak_kernel = OrthogonalAdditiveKernel(base_kernels, max_order=3)

mean_function = gpx.mean_functions.Zero()

prior = gpx.gps.Prior(mean_function=mean_function, kernel=oak_kernel)

likelihood = gpx.likelihoods.Gaussian(num_datapoints=num_train)

posterior = prior * likelihood

negative_mll = lambda posterior, data: -gpx.objectives.conjugate_mll(posterior, data)

opt_posterior, history = gpx.fit_scipy(

model=posterior,

objective=negative_mll,

train_data=train_data,

trainable=Parameter,

)

latent_dist = opt_posterior.predict(

X_test, train_data=train_data, return_covariance_type="diagonal"

)

predictive_dist = opt_posterior.likelihood(latent_dist)

predictive_mean = predictive_dist.mean

Optimization terminated successfully.

Current function value: 107.174483

Iterations: 56

Function evaluations: 60

Gradient evaluations: 60

Sobol indices

We now compute the analytic Sobol indices for each interaction order. These indicate what fraction of the posterior variance is explained by first-order (main) effects, second-order interactions, and so on.

noise_variance = float(jnp.square(opt_posterior.likelihood.obs_stddev[...]))

fitted_kernel = opt_posterior.prior.kernel

sobol_values = sobol_indices(fitted_kernel, X_train, y_train, noise_variance)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 3))

orders = jnp.arange(1, len(sobol_values) + 1)

ax.bar(orders, sobol_values, color=colours[1])

ax.set_xlabel("Interaction order")

ax.set_ylabel("Sobol index")

ax.set_title("Sobol indices by interaction order")

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(1, len(sobol_values) + 1))

[<matplotlib.axis.XTick at 0x7fed91f8f150>,

<matplotlib.axis.XTick at 0x7fed9097eb50>,

<matplotlib.axis.XTick at 0x7fed93597390>]

Typically the first-order (main) effects dominate, with higher-order interactions contributing progressively less. This validates the additive modelling assumption for this dataset.

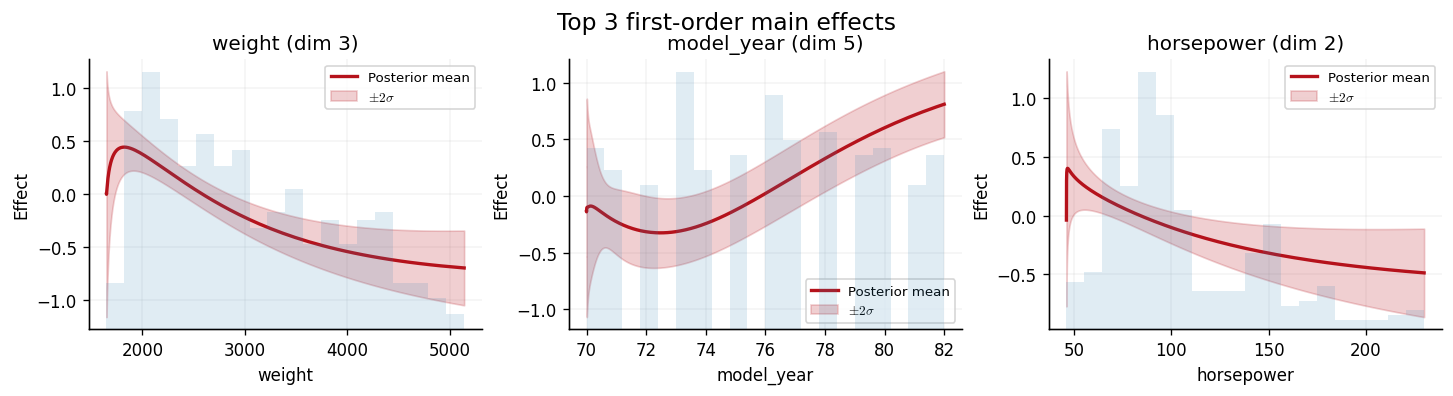

Decomposed additive components

One of the key advantages of the OAK model is the ability to visualise each feature's individual contribution to the prediction. We extract the top 4 first-order main effects and plot the posterior mean and a \(\pm 2\sigma\) credible band for each, alongside a histogram of the training inputs.

For each feature \(d\), we evaluate the constrained kernel \(\tilde{k}_d(x_*, X_{\mathrm{train},d})\) between a 1-D grid and the training points, then form the conditional mean and variance in the usual GP way.

num_top_features = 3

num_grid_points = 300

feature_scores = rank_first_order(fitted_kernel, X_train, y_train, noise_variance)

top_feature_indices = jnp.argsort(-feature_scores)[:num_top_features]

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=num_top_features, figsize=(12, 3))

for plot_idx, ax in enumerate(axes.flat):

feature_dim = int(top_feature_indices[plot_idx])

feature_name = feature_names[feature_dim]

grid_low = float(X_train[:, feature_dim].min())

grid_high = float(X_train[:, feature_dim].max())

grid = jnp.linspace(grid_low, grid_high, num_grid_points)

effect_mean, effect_variance = predict_first_order(

fitted_kernel, X_train, y_train, noise_variance, feature_dim, grid

)

effect_std = jnp.sqrt(effect_variance)

grid_original_scale = flows[feature_dim].inv(grid)

ax.plot(

grid_original_scale,

effect_mean,

color=colours[1],

linewidth=2,

label="Posterior mean",

)

ax.fill_between(

grid_original_scale,

effect_mean - 2 * effect_std,

effect_mean + 2 * effect_std,

alpha=0.2,

color=colours[1],

label=r"$\pm 2\sigma$",

)

histogram_ax = ax.twinx()

histogram_ax.hist(

X_train_original[:, feature_dim],

bins=20,

alpha=0.15,

color=colours[0],

density=True,

)

histogram_ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xlabel(feature_name)

ax.set_ylabel("Effect")

ax.set_title(f"{feature_name} (dim {feature_dim})")

ax.legend(loc="best", fontsize=8)

fig.suptitle(f"Top {num_top_features} first-order main effects", fontsize=14, y=1.05)

Text(0.5, 1.05, 'Top 3 first-order main effects')

Each panel shows how the OAK model attributes predictive variation to individual features. Features with large, clearly non-zero effects are those that the model identifies as important for predicting fuel consumption. The uncertainty bands widen in regions where training data are sparse, reflecting the GP's epistemic uncertainty.

System configuration

Author: Thomas Pinder

Last updated: Thu, 05 Mar 2026

Python implementation: CPython

Python version : 3.11.14

IPython version : 9.9.0

gpjax : 0.13.6

jax : 0.9.0

jaxtyping : 0.3.6

matplotlib: 3.10.8

numpy : 2.4.1

ucimlrepo : 0.0.7

Watermark: 2.6.0